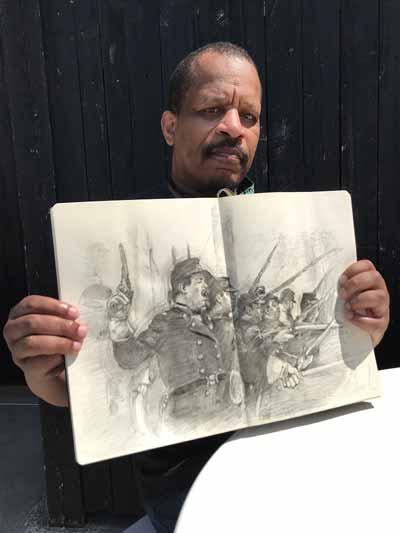

Portrait of Thomas Nast by Paul Szep © 2020 Used with permission of Paul Szep. All rights reserved.

Thomas Nast defined American political cartoons in the decades following the Civil War. His illustrations popularized icons such as the Republican elephant, the Democratic donkey, and even the modern image of Santa Claus. This exhibition highlights Thomas Nast’s remarkable impact through a cartoon biography created by local artists.

A German immigrant who arrived in New York City as a young boy, Nast was working as an illustrator by his mid-teens. His drawings for the immensely popular Harper’s Weekly magazine changed national attitudes and swayed political races. He first became famous for his support of the Union cause in the Civil War and his relentless campaign against New York’s Tammany Hall political machine.

The Boston Comics Roundtable, a community of comics creators, has been meeting weekly since 2006. They collaborated on the following series of cartoons depicting important moments in Nast’s life and career.

Banner image is a self-portrait of Thomas Nast, detail from: “'Continue That I Broached in Jest.'--Shakespeare” Political cartoon, engraving drawn by Thomas Nast. Full image

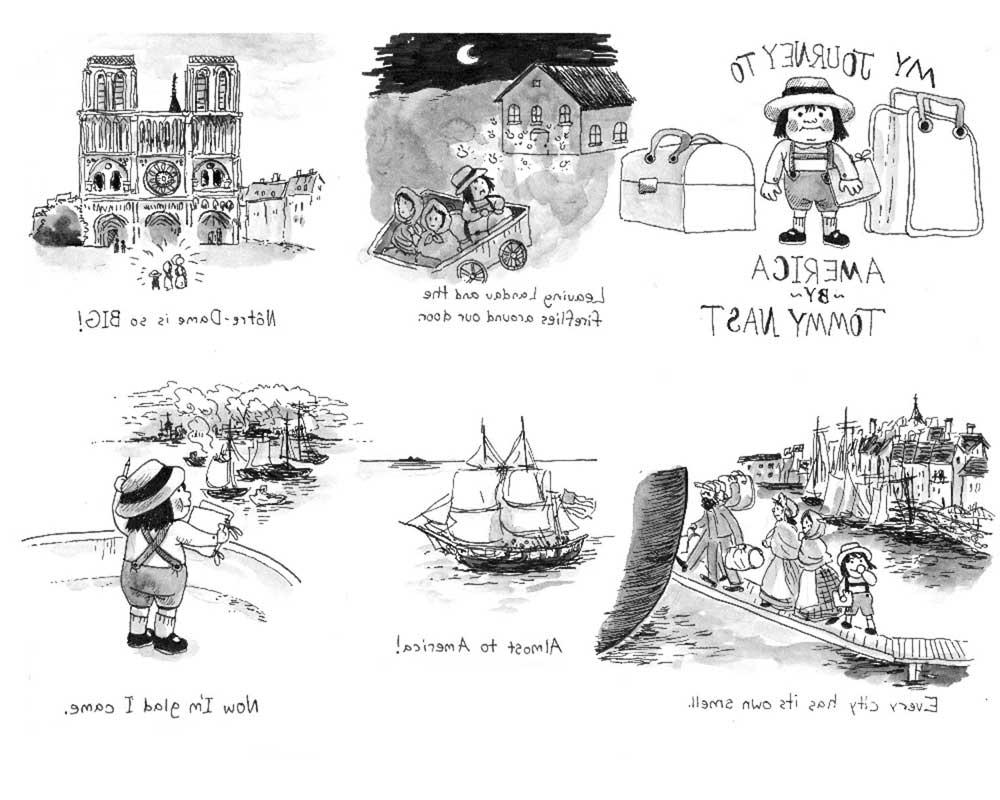

Young Nast immigrates to the U.S. | Catalina Rufin

As a young boy, Thomas Nast immigrated to the United States from Landau, a Bavarian city that today is part of Germany.

At about the age of six, Thomas Nast immigrated to America from Landau, a Bavarian city that today is part of Germany. For political reasons, his father, a military trombonist, left the city and went to sea. Thomas traveled through France with his mother and older sister, sailing to America late in 1846. The Nasts made a new home in New York City, and Thomas’s father rejoined the family four years later.

In 1860, the New York Illustrated News sent 20-year-old Nast to Europe to draw pictures of a famous prize fight and Giuseppe Garibaldi’s campaign to reunify Italy. Nast sketched a “pictorial souvenir” of his voyage, first published after his death in Albert Bigelow Paine’s 1904 biography of him. Catalina Rufin used that illustration as inspiration for this depiction of Nast’s earlier journey as a young boy to America.

About the Artist: Catalina Rufin

Catalina Rufin is a graduate of the Center for Cartoon Studies and Suffolk University. They make comics, done in watercolor, on a variety of subjects such as running, sword-and-sorcery, and memoir. Catalina regularly exhibits and appears on panels at comic conventions around North America.

Their comics and illustrations can be found on @fairywarriorcat on Instagram and Twitter.

Look Further: a “Pictorial Souvenir”

About Nast's “Pictorial Souvenir of the Voyage to Europe, 1860.”

Young Thomas Nast drew a visual account of his journey to Europe in 1860 to document a prize fight and observe the war of unification and independence in Italy. Catalina Rufin has used these drawings as a source for her cartoon of the Nast family’s voyage from Europe to America in 1846.

“Pictorial Souvenir of the Voyage to Europe, 1860.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. Printed in Th. Nast: His Period and His Pictures by Albert Bigelow Paine. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1904, p. 34.

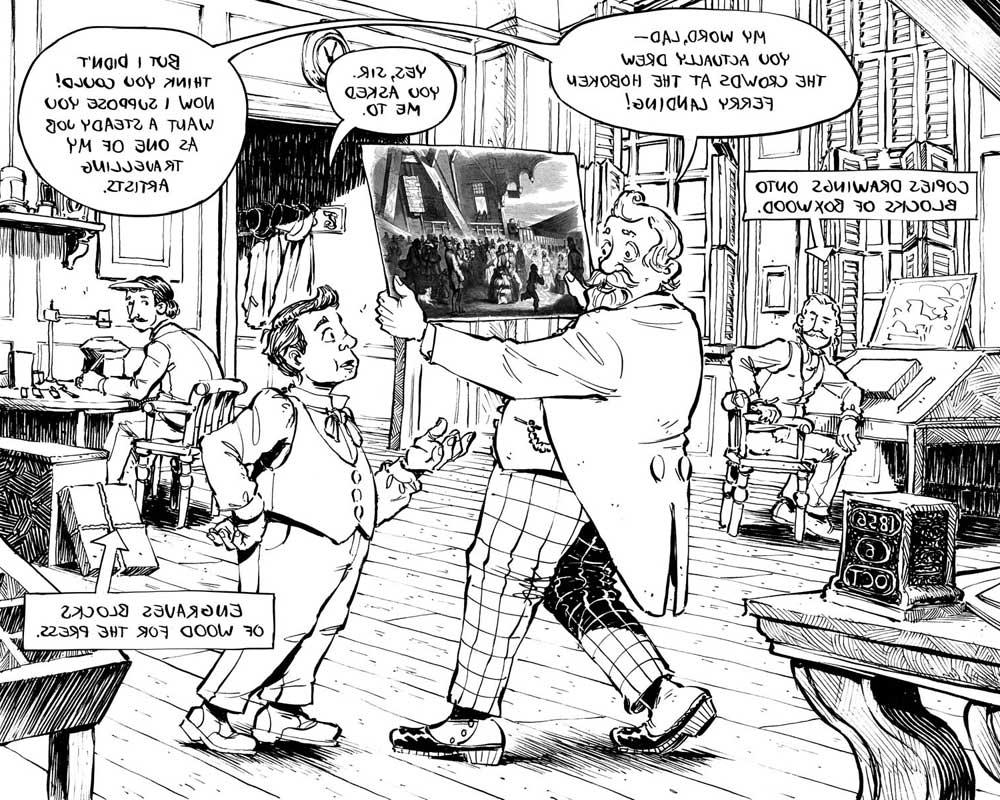

Teenager Thomas Nast draws the attention of Frank Leslie | Jerel Dye

The famed publisher Frank Leslie gave Thomas Nast his first assignment, a drawing of the Hoboken ferry.

Frank Leslie (born Henry Carter) was a British immigrant. Working in Boston in the late 1840s, he developed a faster technique for creating woodblock engravings by dividing the wood and the work among several engravers. After a “traveling artist” like young Thomas Nast drew a scene, a second artist (or, in this case, Nast himself) redrew the picture in reverse on a surface made of small blocks of smooth boxwood screwed together. A two-page spread in a magazine could require up to 20 blocks. The next step was for a team of engravers to etch away parts of each dense woodblock so that only the lines of the drawing remained.

About the Artist: Jerel Dye

Jerel Dye has produced several self-published mini comics and comics stories for anthologies like Inbound, Minimum Paige, Hellbound, and the award-winning Little Nemo/Winsor McCay tribute Dream Another Dream. In 2012, he received the MICE comics grant for his mini-comic From the Clouds. Pigs Might Fly, his first graphic novel, was released in 2017 by First Second Books. Much of his art stems from a deep interest in science and technology, though it frequently contains a healthy dose of wonder. He received his BFA in painting from UMass Dartmouth and his MFA from MassArt in the Studio for Interrelated Media.

You can see more of his work at www.artstation.com/jereldye.

Look Further: "Hoboken, N.J.—The Elysian Fields"

Earliest Known Published Drawing of Thomas Nast

In 1856, Thomas Nast auditioned for a job with Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper by drawing passengers from New York City on their way to a Sunday outing at the Elysian Fields—a resort in New Jersey.

“Hoboken, N. J.—The Elysian Fields.—Great Rush of Visitors on Sundays.” Engraving drawn by Thomas Nast. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 11 October 1856, page 277.

How Wood Engravings Were Made

This blog post illustrates how wood engravings for 19th–century newspapers and magazines were made.

How Wood Engravings Were Made [Blog]. Graphic Arts Collection, Special Collections, Firestone Library, Princeton University.

A discussion between Nast and President Lincoln | Shea Justice

Thomas Nast was an ardent supporter of the Union cause and his illustrations were of great aid in recruiting soldiers for the war effort.

In 1862, Thomas Nast joined the staff of Harper’s Weekly. His pictures of the Civil War became extremely popular, and he stayed with the magazine for 25 years. Rather than depicting the fighting realistically, as other artists did, Nast drew allegorical or emblematic scenes. He celebrated the Union Army’s path to victory, but also drew sentimental vignettes—which were often paired—of camp life and the home front.

About the Artist: Shea Justice

Shea Justice grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts. As a child, he developed a passion for art from watching Drawing from Nature on PBS and reading comic books. After attending Boston University, where he earned a BFA in art education, he taught in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and in the Boston Public Schools system. He later got an MFA from the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University. Currently he is a teacher at Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School. Shea has participated in art exhibitions throughout the Boston area, and his work is permanently on display at the Sudbury Public Library and the Grove Hall Library. For the last 20 years, he has been a member of Northeastern University’s African American Master Artists-in-Residence Program (AAMARP).

Look Further: “Sgt.” Nast and Pres. Lincoln

Nast's Civil War cartoons for Harper's Weekly

During the Civil War, Thomas Nast drew many patriotic and sentimental scenes of Union soldiers freeing enslaved people in the South, and marching “on to Richmond” and victory; but also of them separated from home and family by their service—or even by death. Nast was reported to have had an interview with Pres. Lincoln, who, according to the story, described him as “our greatest recruiting sergeant.”

“Emancipation of the Negroes.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 24 January 1863, p. 56-57.

“On to Richmond.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 18 June 1864, p. 392-393.

“Dedicated to the Chicago Convention” [also known as "Compromise with the South”]. Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 3 September. 1864, page 572.

About the Historian Who Appears in the Lower Right Corner

Nast biographer Fiona Deans Halloran, an authority on his life and career, appears in a “cameo role” in the lower right-hand corner of Shea Justice’s cartoon where she casts doubt about Nast’s interview with Pres. Lincoln.

“From Santa to the Civil War: Fiona Deans Halloran on the Political Cartoons of Thomas Nast” by Ashley Whitehead Luskey. [Web post with interview] The Gettysburg Compiler On the Front Lines of History.

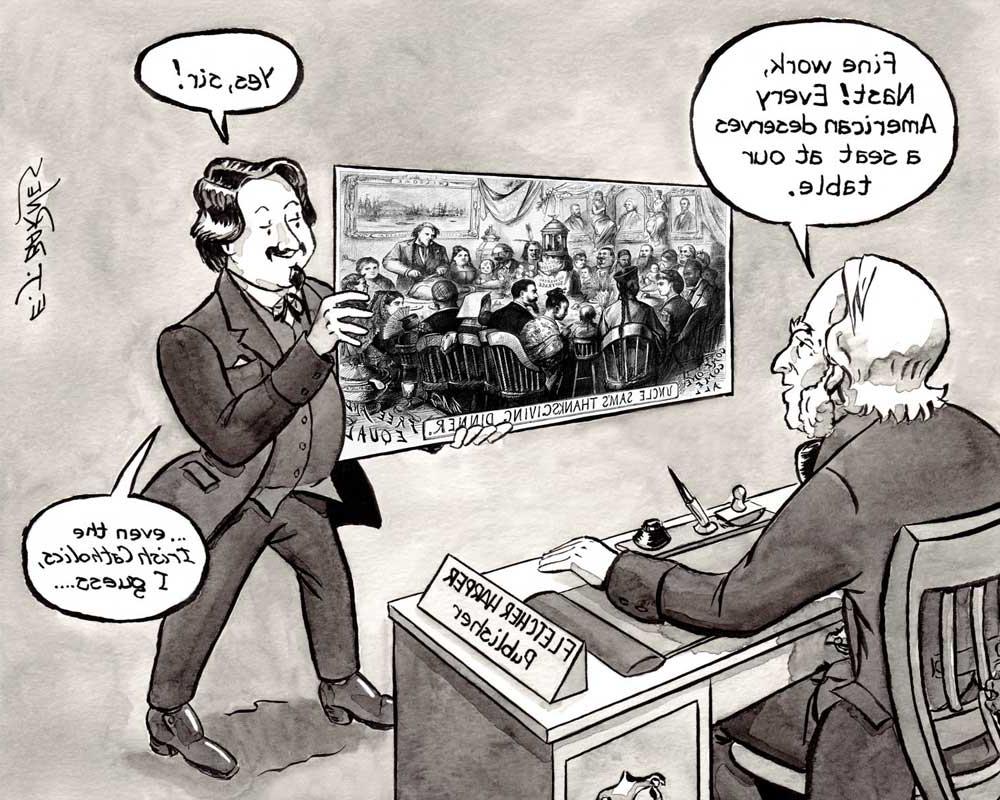

Nast displays his “Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner” | E. J. Barnes

Thomas Nast drew an optimistic vision of representatives of many different ethnic, immigrant, and minority groups gathered around a table for a traditional Thanksgiving dinner.

Until his death in 1877, Harper’s Weekly publisher Fletcher Harper gave Thomas Nast wide editorial freedom. During Reconstruction, Nast’s cartoons championed full civil rights for newly freed African Americans, Chinese workers in the West, and other ethnic immigrants and minorities. However, Nast still drew upon stereotypes as shorthand to convey his political ideas. He was known to attack the women’s suffrage movement, but his most vitriolic caricatures were often of Catholic clergymen and Irish Americans.

About the Artist: E. J. Barnes

Illustrator, cartoonist, animator, and sequential artist E. J. Barnes served as a local affairs editorial cartoonist for the Recorder, based in Greenfield, Massachusetts, from 2005 to 2009. Her political and gag cartoons have been published in various outlets, including the Cambridge Chronicle, Funny Times, Fortean Times, and the Journal of Irreproducible Results. She works in ink, ink wash, watercolor, and scratchboard. Her home studio is in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her work can be found at www.ejbarnes.com and www.drownedtownpress.com.

Look Further: Nast’s “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” in close up

Explore “Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner.” Drawn by Thomas Nast.

Thomas Nast’s drawing, as it appeared in Harper’s Weekly, contains many small, but telling details: the bunting above the portraits of Nast’s heroes—Lincoln, Washington, and Grant—is inscribed “15th Amendment,” while the centerpiece reads “Self Government” and “Universal Suffrage.” A youthful “Uncle Sam” and “Columbia” (who bears a strong resemblance to Nast’s wife, Sallie Edwards Nast) host their diverse dinner guests beneath a “welcoming” view of Castle Garden in New York City, the point of arrival for many immigrants.

“Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 20 November 1869, page 745.

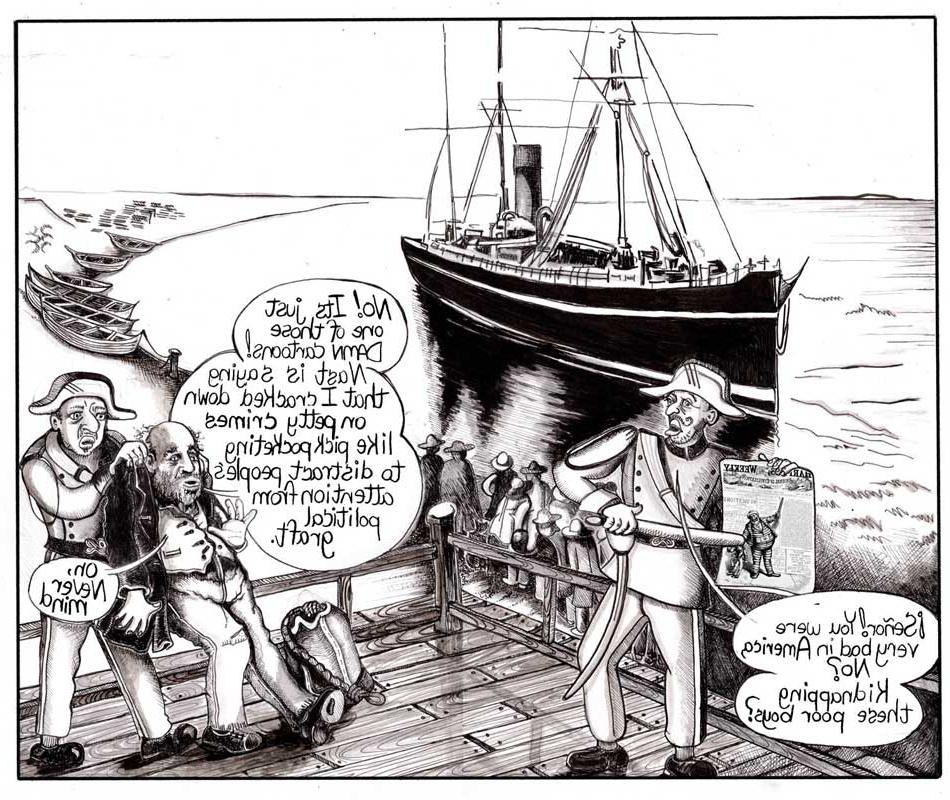

Fugitive “Boss” Tweed is recognized from a Nast cartoon | Heide Solbrig

A Spanish policeman holds a copy of the 1 July 1876 issue of Harper’s Weekly with Thomas Nast’s “Tweed-le-Dee and Tilden-Dum” cartoon on the cover as he arrests “Boss” Tweed, who protests that he’s not as guilty as the cover suggests.

Thomas Nast and Harper’s Weekly waged a ferocious editorial campaign against New York’s Tammany political machine, because it was both corrupt and a Democratic power base. In particular, Nast attacked William M. “Boss” Tweed. In 1873 Tweed was convicted of graft and served a year in prison. Sued by the state of New York, he fled to Spain where officials identified Tweed from a Nast drawing on the cover of Harper’s—although, based upon the cartoon, they thought he had been charged with child abduction. Tweed returned to the United States and died in prison in 1878.

About the Artist: Heide Solbrig

Heide Solbrig is a nonfiction cartoonist, writer, and media scholar. She received her MFA from San Francisco State University and her PhD in Communications from UC San Diego. She is producing a comics series based on interviews from Fabens and Tornillo, Texas, and a memoir about the suburbs in the 1970s. In addition, she works with the legal team for BIJAN, the Boston Immigrant Justice Accompaniment Network, to assist immigrants in detention.

Her work can be found at www.heidesolbrig.com.

Look Further: Boss Tweed is Undone by “Them Damned Pictures”

Nast roasts Boss Tweed in Harper's Weekly

Thomas Nast’s crusade against the Tweed Ring in Harper’s Weekly reached its climax during the 1871 New York City election. Nast produced a series of large and small cartoons—often several cartoons in each issue—depicting Boss Tweed’s iron grip on political power through bribery and voter fraud. Each Nast drawing was powerful, but their cumulative effect was overwhelming.

“Tweed-le-Dee and Tilden-dum.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper’s Weekly, 1 July 1876, page 525.

“'That's What's the Matter.' Boss Tweed. 'As long as I count the Votes, what are you going to do about it? say?'” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper’s Weekly, 7 October 1871, page 944.

“The 'Brains.' That Achieved the Tammany Victory at the Rochester Democratic Convention.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper’s Weekly, 21 October 1871, page 992.

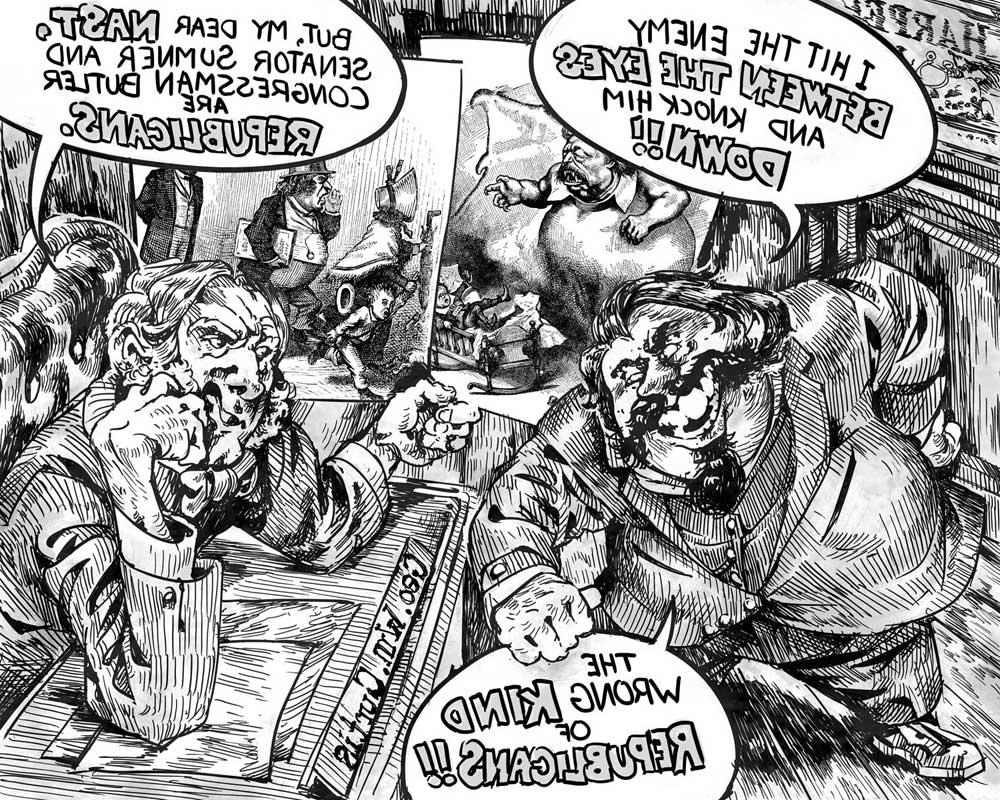

Nast caricatures Benjamin Butler and Charles Sumner | Sam Cleggett

Harper’s Weekly editor George William Curtis expresses his distaste for Nast’s caricatures of Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler.

Thomas Nast saw Ulysses S. Grant as a military and political hero. His cartoons attacked not only Grant’s Democratic opponents but also liberal Republicans who organized against him. Among the Republicans who inspired Nast’s ire were two from Massachusetts: Sen. Charles Sumner and Rep. Benjamin F. Butler. Sumner pushed harder for Black civil rights than President Grant (and Nast) thought practical; ironically, within a few months after Sumner’s death in 1874, Grant signed the Civil Rights Act that the senator had sponsored.

Butler supported votes for women and paper money--and had co-sponsored the Civil Rights Act in the House of Representatives--but was also a notoriously corrupt political opportunist. In 1882 Butler finally won a gubernatorial race as the candidate of the Greenback, Labor, and Democratic Parties.

About the Artist: Sam Cleggett

Sam Cleggett is a cartoonist and animator living in Boston, Massachusetts. He enjoys burnt coffee, autumn rain, and the incoherent warbles of wild turkeys. He has a healthy interest in the historical vernacular architecture of Brighton, Massachusetts, and endeavors to include more of it in his works. He loves and emulates the hatched texture of woodcuts and lithography, even though it is hard on the wrist.

His illustrations can be found at www.samcleggett.com.

Look Further: Nast Caricatures Hypocritical Massachusetts Politicians

Depictions of Hypocrites and Political Opportunists

Thomas Nast drew for a national audience, but he caricatured leading Massachusetts Republicans as hypocrites: Charles Sumner for his “high-minded” attacks on Pres. Grant’s moral failings and Representative Benjamin F. Butler for his political opportunism. During the Civil War, Nast began by drawing Butler in a positive light, but, over time, Nast cruelly satirized him as both monstrous and ridiculous.

“The Battle-Cry of Sumner.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Th. Nast: His Period and His Pictures by Albert Bigelow Paine. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1904, p. 229.

“The Cradle of Liberty in Danger.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. Harper's Weekly, 11 April 1874, p. 309.

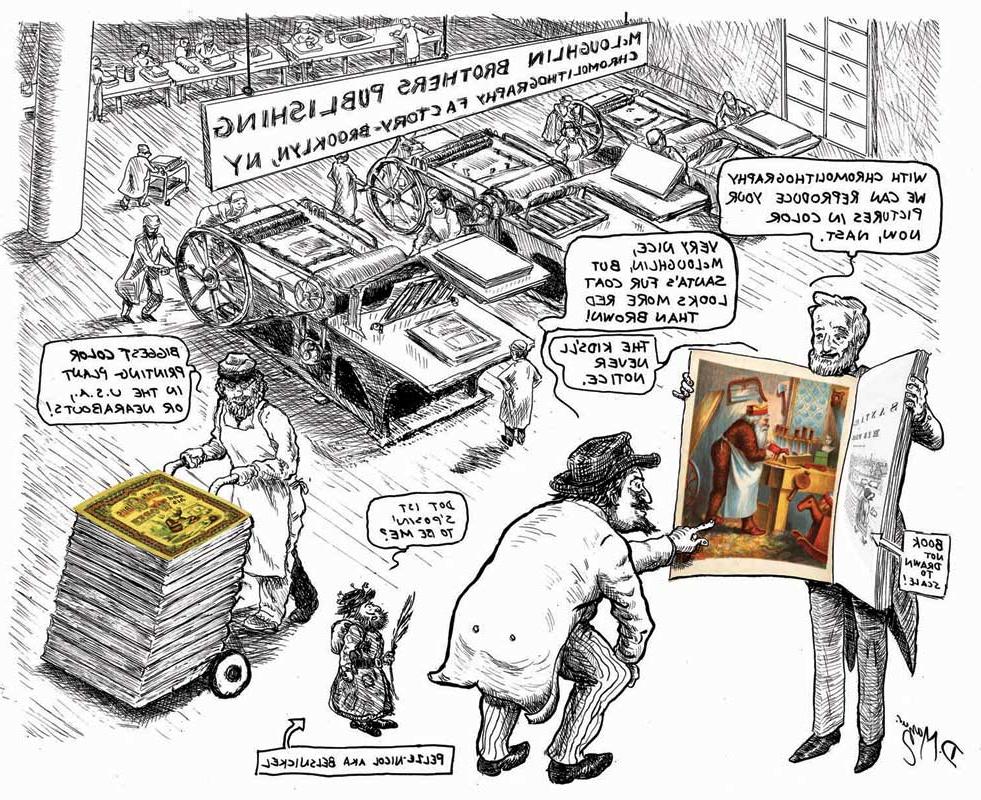

Nast's Santa Claus gets a red suit | Dan Mazur

Publisher John McLoughlin, Jr., shows Thomas Nast a chromolithographic illustration for Santa Claus and His Works.

Images of Santa Claus and His Works from University of Florida, http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00026648/00001.

Thomas Nast helped popularize the figure of Santa Claus in American culture. He pulled details from the Pelze-Nicol legends he had heard as a little boy in Landau and from New York’s own Santa Claus traditions. Nast’s Santa Claus was child sized—still an “elf.” He made it standard for Santa to have a white beard and to wear a fur coat with a big buckle, and he was the first to show him living at the North Pole.

About the Artist: Dan Mazur

Dan Mazur is an independent cartoonist, editor, publisher, educator, and author who lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His graphic novel Lunatic will be published by Fanfare Press in 2020. He is the co-writer, with Alexander Danner, of Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present, published by Thames & Hudson. He is a co-founder of the Boston Comics Roundtable and MICE: the Massachusetts Independent Comics Expo and the founder of Ninth Art Press, a small press devoted to comics and comics anthologies.

His work can be found at www.danmazurcomics.com.

Look Further: Nast's Popular Iconography

Santa Claus

Thomas Nast began his long connection with the image of Santa Claus by showing him, outfitted in an American flag, visiting Union soldiers in camp at Christmas 1862. Even after his fame as a political cartoonist faded, Nast continued to draw or paint Santa, or illustrate books about him.

“Santa Claus in Camp.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 3 January 1863, p. 1.

Image of Santa Claus [page 3] from Santa Claus and His Works by George P. Webster. (NY: McLoughlin Brothers).

Tammany Tiger

Thomas Nast popularized the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant as political party symbols, and made the Tammany tiger, the emblem of a firefighting club associated with the Tammany Ring in New York, the symbol of ferocious and destructive political corruption.

“The Tammany Tiger Loose—‘What are you going to do about it?’” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 11 November 1871, p. 1056-1057.

The Elephant and Donkey

The elephant and donkey appeared together in a Nast cartoon for the first time in 1879. By the 1880 presidential election, Nast could no longer sustain the argument that the Republican elephant was the symbol of superior virtue, although the Democratic donkey still threatened to plunge the country into financial chaos.

“Stranger Things Have Happened.” Drawn by Thomas Nast. From Harper's Weekly, 27 Dec. 1879, p. 1001.

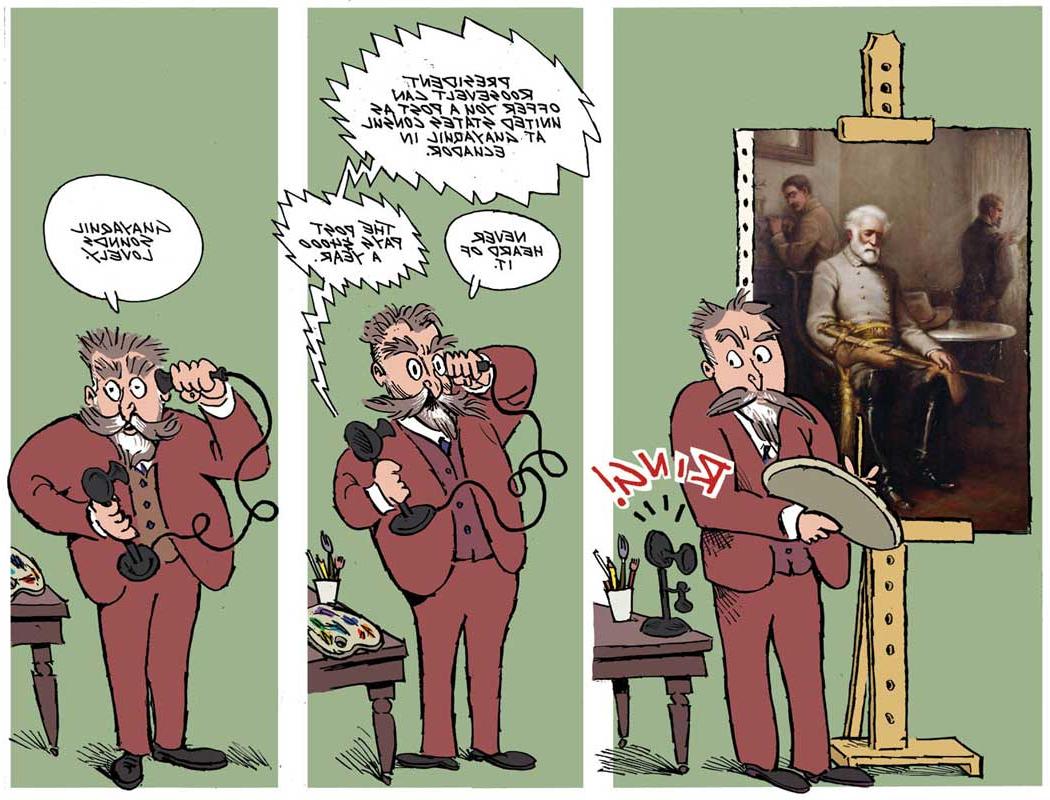

Nast becomes a consul to Ecuador | Nick Thorkelson

With Thomas Nast’s artistic career in decline, Pres. Theodore Roosevelt offered him the post of U.S. Consul at Guayaquil in Ecuador.

Image of painting, Lost cause: Lee waiting for Grant, courtesy Chicago History Museum, ICHi-066261.

Thomas Nast left Harper’s Weekly in 1887, frustrated by his shrinking editorial freedom. He tried to start his own magazine, but it failed, as had his investments in a Colorado silver mine and the financial firm of President Grant’s son, Ulysses, Jr., which ruined both Nast and the former president. Now nearing 60, Nast searched for a steadier income to support his family. He received sporadic magazine commissions and worked on a series of paintings about the Civil War, including one of the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

When Theodore Roosevelt, who as a boy had enjoyed Nast’s cartoons, became president, he offered Nast a diplomatic post—a common way to reward party loyalists. Seeing no better prospects, Nast became the U.S. Consul at Guayaquil in Ecuador in 1902, where after only four months he died of yellow fever.

About the Artist: Nick Thorkelson

Nick Thorkelson’s latest work, Herbert Marcuse: Philosopher of Utopia, came out from City Lights Books in 2019. He is now working on a second graphics biography about William Morris. He has done political cartoons for the Boston Globe and for many advocacy groups. He collaborated with Harvey Pekar on nonfiction comics in the anthologies The Beats and Studs Terkel’s Working. Other publications include The Earth Belongs to the People, The Underhanded History of the USA, The Legal Rights of Union Stewards, Economic Meltdown Funnies, Fortune Cookies, and The Comic Strip of Neoliberalism.

His work can be found at www.nickthorkelson.com.

Look Further: Thomas Nast Revisits the Surrender at Appomattox

Nast's Depictions of General Lee

Nast had marked the Civil War surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox in 1865 with a Palm Sunday cartoon in Harper's Weekly. Two decades later, Nast depicted General Lee in two oil paintings. Nast had left Harper's Weekly in the mid-1880s, had fallen on hard times, and was selling oil paintings of historic events. In one painting he finished around 1885, Nast depicted General Lee seated, waiting in Appomattox Court House for the arrival of General Grant. In 1896, Nast revisited the surrender of Lee's army, but made it more of a reconciliation of North and South, rather than an act of Christian charity to the “foes of the Union.”

“Lost Cause: Lee waiting for Grant” painting by Thomas Nast, circa 1885. From the Chicago History Museum.

“Peace in Union” painting by Thomas Nast, 1895. From the Galena History Museum website.

Thomas Nast: A Life in Cartoons was produced as a part of our Who Counts? a Look at Voter Rights through Political Cartoons online exhibition.